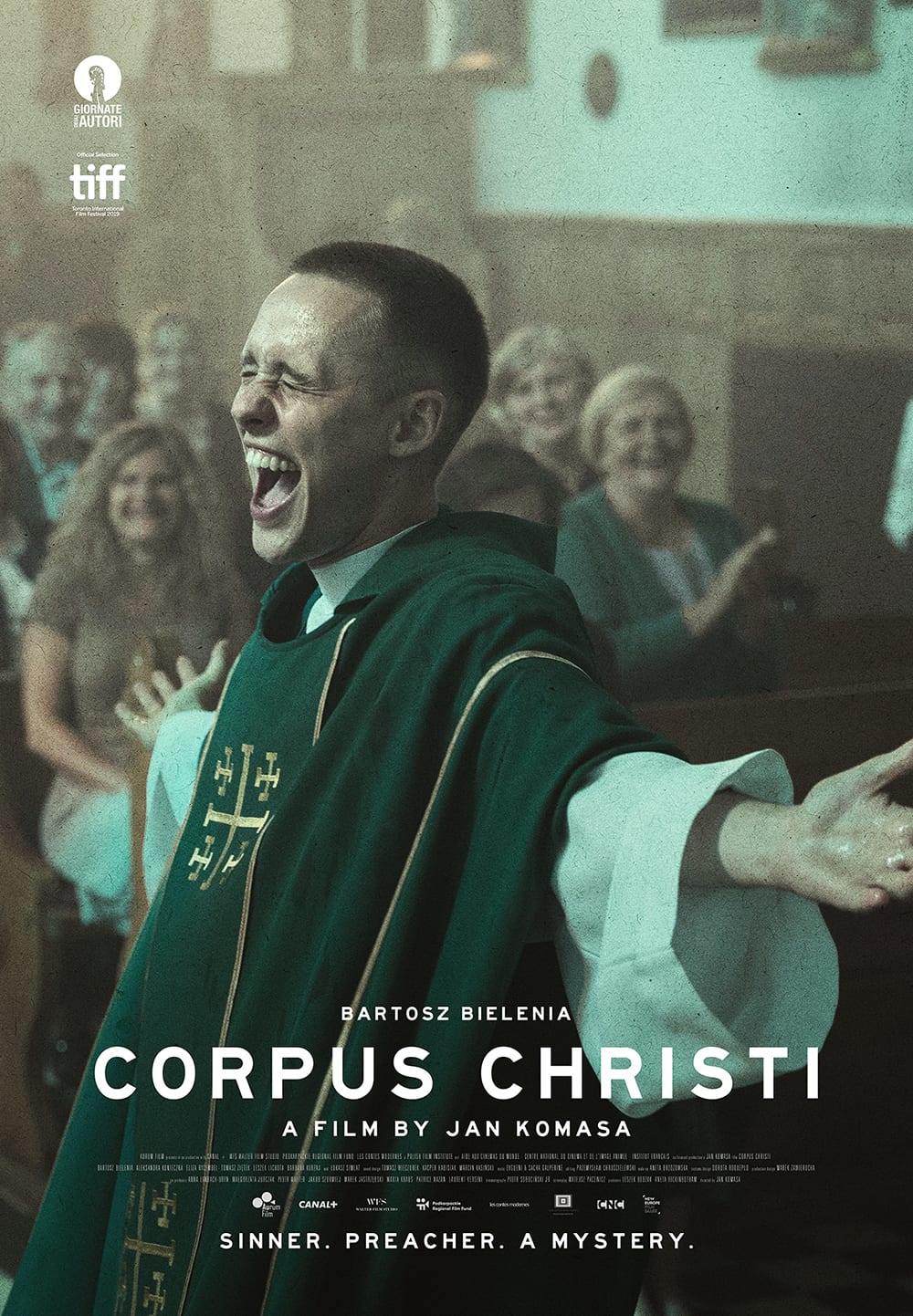

Corpus Christi – The Body of Christ

?Each of us is a priest of Christ. Me, you. Each and every one of you.? Oscar-nominated Corpus Christi (for Best International Feature Film) explores what it means to be a priest of Christ. But it does so through the story of an imposter who finds a community in need. The story is inspired by…