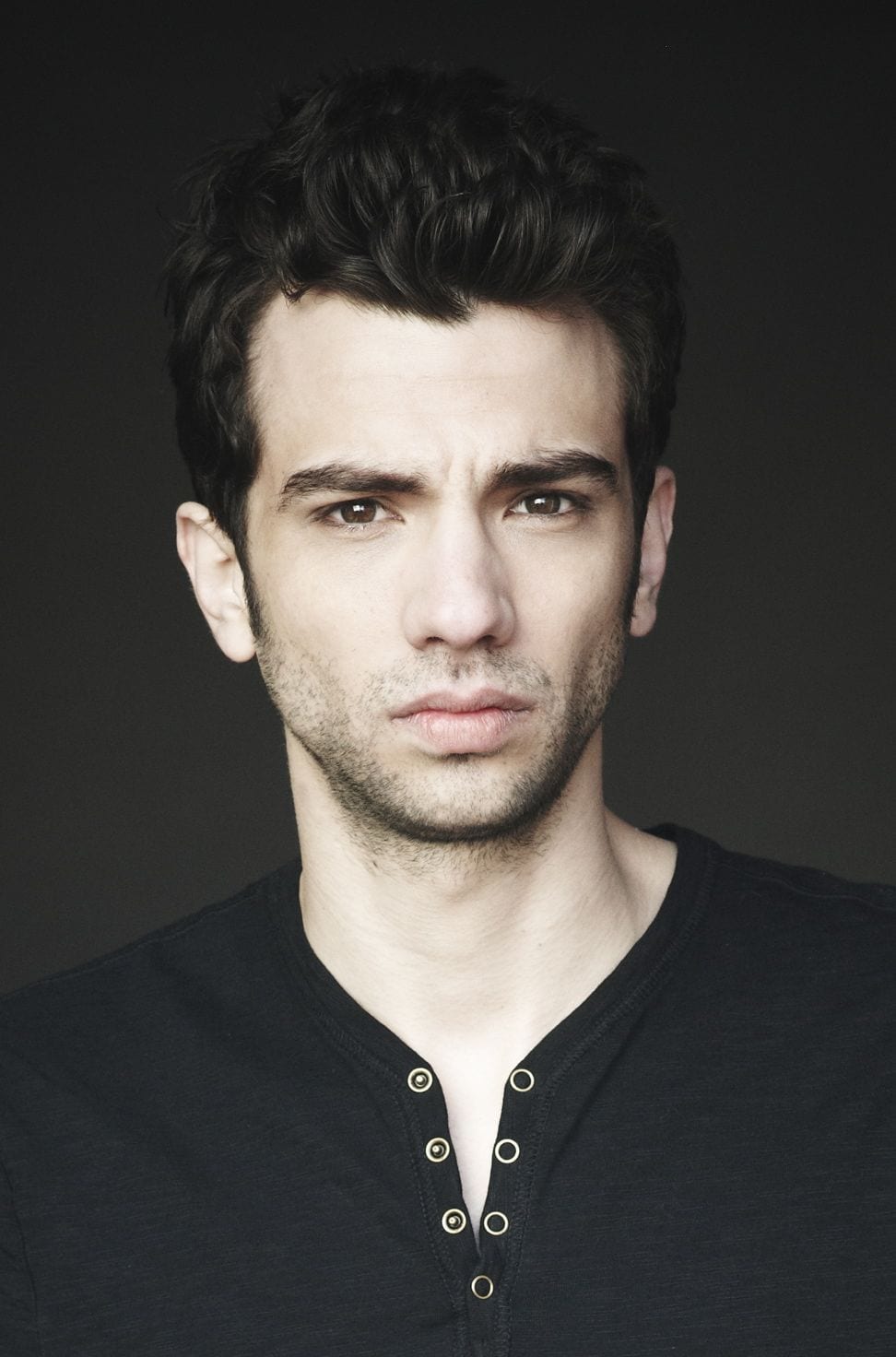

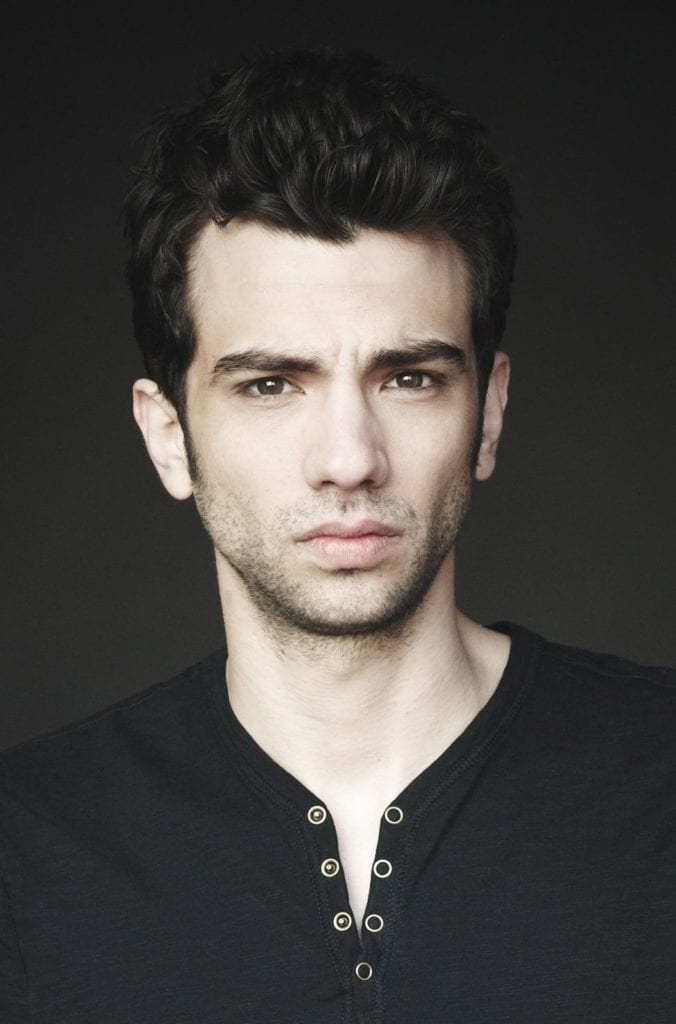

It takes a lot to scare Jay Baruchel.

As a long-time fan of horror, he believes that the genre has fallen creatively stagnant as of late. So, he decided to take matters into his own hands.

With Random Acts of Violence, his latest turn in the director?s chair, Baruchel (who also co-wrote the script with friend, Jesse Plemons) decided to take matters into his own hands and create the type of film he wanted to see onscreen. Though Violence does not fail to offer all the blood and gore that the title suggests, it also maintains a psychological edge that drives the narrative. Having passionately crafted the film over the last decade with friend Jesse Chabot, he could not resist the opportunity to create something unique that fought against the current trends that he has seen onscreen.

?As a fan of the genre, I find myself just rarely scared by anything that I see,? Baruchel observes. ?Rare is the horror film that is a good movie and actually scares me. I just also kind of developed a bit of a personal distaste for this kind of idea of what a horror film had to be. Basically like 10 or 15 years ago, a bunch of investors realized that they could put a little money into something that would make them a bunch. Then, all of a sudden, we had this rash of self-contained genre films, which are very transparent in why they were created. For me, it’s an art form that is terribly important to me and I cannot separate my love of cinema from my love of horror movies. I think, when it’s at its best, it’s a very pure, very direct art form and it lends itself to some pretty special stuff. So, I just tried to make the movie that I wished was out there.?

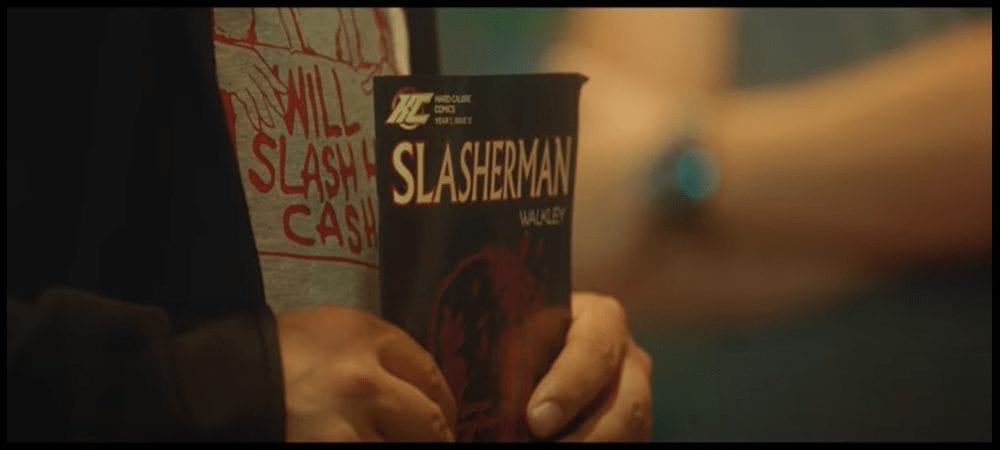

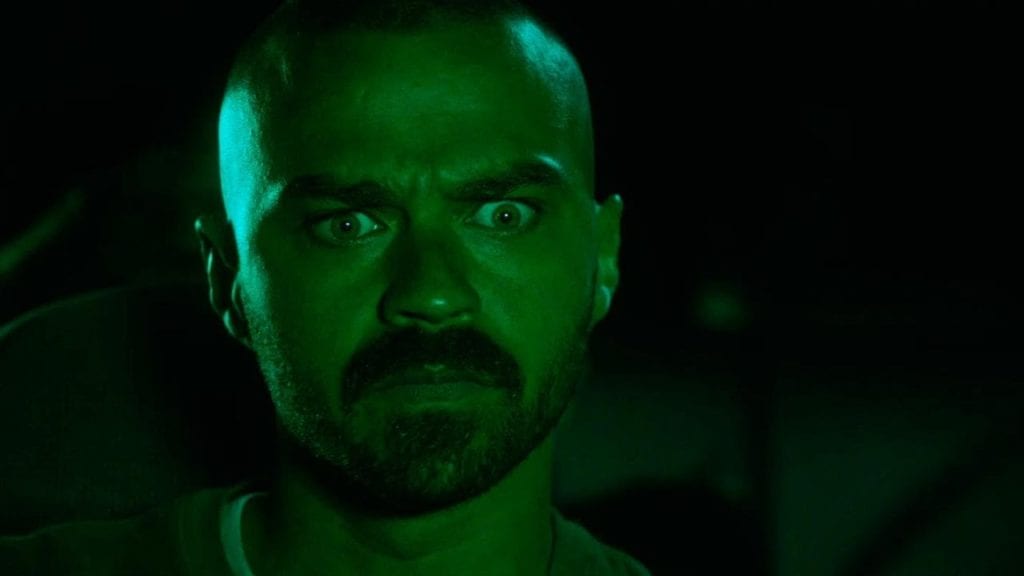

Random Acts of Violence tells the story of Todd Walkley (Jesse Williams), the creator of Slasherman, an R-rated comic book series based on a real-life serial killer. Having decided to end his wildly successful series, he ventures out onto a press tour with his publicist, Ezra (Baruchel) and his girlfriend, Kathy (Jordana Brewster) in order to promote the final issue. Along the way, they visit the town where the original Slasherman caused so much harm in the past and inadvertently awaken the same murderous beast that Todd?s story sought to idolize.

While Baruchel has a deep love of horror, he also maintains a passion for the world of comic books. (He even recently invested in Chapterhouse?s revival of classic Canadian hero, Captain Canuck.) Based on a comic of the same name, Random Acts of Violence finally gave him the opportunity to bring a comic to life onscreen himself. Given his experience in the industry, he felt like he could create a story that both celebrates the source material and brings something new to life as well.

?It really starts from there being a really interesting story and staring off viewpoint in the comic book,? Baruchel explains. ?It just got stuck in Jessie’s head and in my head. At a certain point, the only thing that matters is serving the story as well as we can. So, at a certain point, we allow the document we’re creating to start to live its own life, which means it’s beholden to its source material but only to a certain point. There comes a moment where the movie starts to want to be something on its own. You have to decide [if this] thing that it wants to be that is different than the comic is worth doing,?

?In terms of the aesthetics, I think maybe subconsciously, we wanted it to look like that,? he continues. ?But I think, more than anything, our way in with our camera and our lighting and our color palettes was more just kind of arch. We wanted really strong arch colors and light and shadows and that happens to be how a lot of comics are created. So, it ends up looking like that. Now, in terms of what my experience with ChapterHouse and Captain Canuck lent to it, I knew exactly what it would be like to be on a Comic-Con tour and the cramps and headaches that the owner has to look forward to arriving at a venue. So, I think there’s some [place] in the movie where I’m yelling at the guy who owns a comic book shop about a box that he can’t find. That seems to happen at every Comic-Con. That seemed to be a bit of a comic industry banality that could be something funny and real. So, some of my years in admin in that world definitely informed vibes in this movie.?

When he thinks about who has most influenced his work, Baruchel believes that some of the best aspects of the film stem from both the comic world and classic horror cinema. Though most of his examples are well-known classics, his recognition of one of Kubrick?s most famous works stands out as surprising.

?Alan Moore?s [work in] From Hell, I think is as good as use of the comic book medium as has ever been created,? Baruchel points out. ?I would also put Preacher up there. Everything Garth Ennis did for the years that he wrote ThePunisher [is] really, really, really important to me. Then, I would have to say, for horror flicks, it would be The Exorcist, the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre by Tobe Hooper and John Carpenter’s The Thing. To be honest, I think still The Exorcist is probably the scariest movie ever made but I think what might be neck and neck with it [is something that] people don’t think of it as a horror movie. I think I would argue that 2001: A Space Odyssey is probably the scariest movie ever made. So, I will spend my life trying to recreate even a moment from that film.?

As is the case with any work of art, both comic and horror culture are digested and viewed differently with each audience member. For example, while some may celebrate horror for its grit and darkness, others feel uncomfortable and even angered by what they see. In regards to this, Violence opts to discuss the relationship between artist and audience and, in particular, the creative power and responsibility that the creator may (or may not) recognize that they hold.

?It’s an inherently kind of relative experience as an audience member consuming a work of art,? says Baruchel. ?I was trying my best to show every bad thing that can come from this. It was a sort of mental target. It’s more about this idea that one can divorce oneself from responsibility for anything one puts out into the world, which I think is as absurd as the concept that video games and comics make people kill people. I think those are both two very facile, silly, absurd philosophies… When Todd has made a Faustian bargain and even if he thinks that his book is victimized by critics, part of him as a rational man has to agree with at least part of what they’re saying. So, he knows ultimately that even if he believes his work has more merit than people seem to believe it does, he knows what his fan base looks like and he knows ultimately how will come across in the cold light of day. So, it’s about the sort of spectrum of responsibility that he was able to keep at arm?s length, getting closer and closer to him until the end.?

Having said this, one of the great debates surrounding horror films is the distinction between violence as art and fetishizing evil. Asked where he believes the line between exploitation and art lies in the genre, Baruchel believes that, while that line is subjective, it often stems from the author?s sense of authenticity.

?I think it’s a question that we don’t necessarily provide a clear answer to which is deliberate,? he answers. ?I think there’s some stuff which the film kind of takes a specific moral philosophy and standpoint on but there’s other stuff that is more kind of contributing to a debate and a conversation that I feel should happen. That being said, with those movies that I watch, I know in my heart of hearts when something is feels truthful and something feels kind of fetishistic. I’d point to a Quebecois movie, Les 7 Jours du Talion (which is called in English, 7 Days), and that movie is really harsh. It’s just one guy torturing another guy in a room basically for a whole movie and [with a] great degree of realism. That’s a harsh watch but never once does it feel cheap or false. Never once does it feel like a love letter to violence and it doesn’t seem to be sort of wallowing in it. So, to answer the question, I think it’s kind of hard. It’s this almost amorphous thing that we call truth. I think you can tell when something warrants its aesthetic and, I feel, I think you can [tell] when it is ugly for the sake of ugly. I think it’s a terribly relative thing because every single one of us watches the same movie [and we are] going to have some different reactions to it. So, that would be my kind of instinct is that it speaks to more the truth behind it. [For example,] why Seven is important and a lot of other movies about a serial killer aren’t.?

Within Violence?s healthy dose of blood and gore, it?s also interesting to note the significant amount of religious imagery in the film that is often used to give depth to the murderous mayhem. Having grown up in a religious family, Baruchel recognizes that the emotional challenges of his upbringing serve as an influence within the film?s visuals.

?Basically, I’m kind of a child of two cultures to a degree. My dad is Sephardic Jewish, first generation, and my mom [comes from the] type of Irish, English, Scottish Canadians, and deeply Catholic,? he responds. ?Some of the most impactful, not necessarily best, but most impactful moments in my childhood are tied to religion and Catholicism specifically. I was in Catholic school from Grade One through Six and have hated the entire time as a result of it. I like to tell people that I was raised with two different, but very potent, forms of guilt from Jewish culture and Catholic culture. This is the best way I can say it. I remember my mom reading me the Bible when I was a kid and she got to the story about Noah. I started like bawling my eyes out uncontrollably. At three years old, [I was] bawling my eyes out. Why would God want to do this? And then, Catholicism has a lot of really beautiful stuff but it is very deeply violent. You grow up going to church and in class and seeing Christ eviscerated and brutalized. It’s drilled into you. So, it’s impossible for me to kind of separate blood from awe, because it was drilled into me from a childhood and from years and years and years in church. My relationship with the church is still kind of like a weird, tenuous one. I reject most of it and yet I still feel a degree of safety and comfort when I’m in one. So, there’s a sort of push and pull in me that kind of finds it finds its way out and manifests itself in this movie.?

Of course, a unique blessing for Baruchel is the chance to film within his home country of Canada. While he admits it might have been easier to work somewhere else, he feels that one of the great blessings of filmmaking is the opportunity to contribute to the cultural make-up of his home country.

?This is my home. It’s where I’m from, and this is where I’m most comfortable,? he begins. ?The other piece of it is I feel what many could call a silly obligation to English Canadian cinema. I want to know that, for better or worse, I contributed to the cinematic language of my country. I want to know that I added something to our kind of cultural tapestry. It would be more convenient, I think, for me to have gone elsewhere potentially but I know that, at the end of the day, even if I got to create some really special stuff, I would’ve contributed to another country’s culture.?

?For me, my great shame is that I never joined the army, if I’m being perfectly frank. That’s not a joke. That’s something [that’s always haunted me since I was a kid, that I didn’t do a lot of my uncles and my granddad and my cousins did. I don’t mean to say that I am comparing this movie to what any of my uncles or grandad or cousins did and join the army but it is, in some way, a way that I can kind of contribute and help. Countries come and go, but art sticks around. I would like to add to this country as best as I can.?

For full audio of our interview with Jay Baruchel, click here.

Random Acts of Violence is available on VOD on July 31st, 2020.