In 1947 hundreds of years of British rule over India came to an end with the creation of two countries: India and Pakistan, and the largest mass population migration in history. Viceroy?s House is a kind of Upstairs/Downstairs view of that history. Director Gurinder Chadha, who was born in Kenya and grew up in London, says that she grew up ?in the shadow of Partition?. Her grandparents were part of that mass migration. Although the events have been covered before, she has found a new way to bring this story to the screen that allows us to not only see the history, but the personal stories of those involved.

The story begins with the arrival of Lord Louis Mountbatten (Hugh Bonneville) who has been tasked with being the ?last Viceroy??to oversee that granting of independence to India. The ?upstairs? part of the story involves Mountbatten, his wife Edwina (Gillian Anderson), daughter Pamela (Lily Travers), and the political situation involving the negotiations with the Indian leaders, Mohandas Gandhi (Neeraj Kabi), Jawaharlal Nehru (Tanveer Ghani), and Muhammed Ali Jinnah (Denzil Smith). While Mountbatten has often been saddled with blame for Partition, this film shows him and his family to be good people in a hard situation?and that he may have been set up to take the blame.

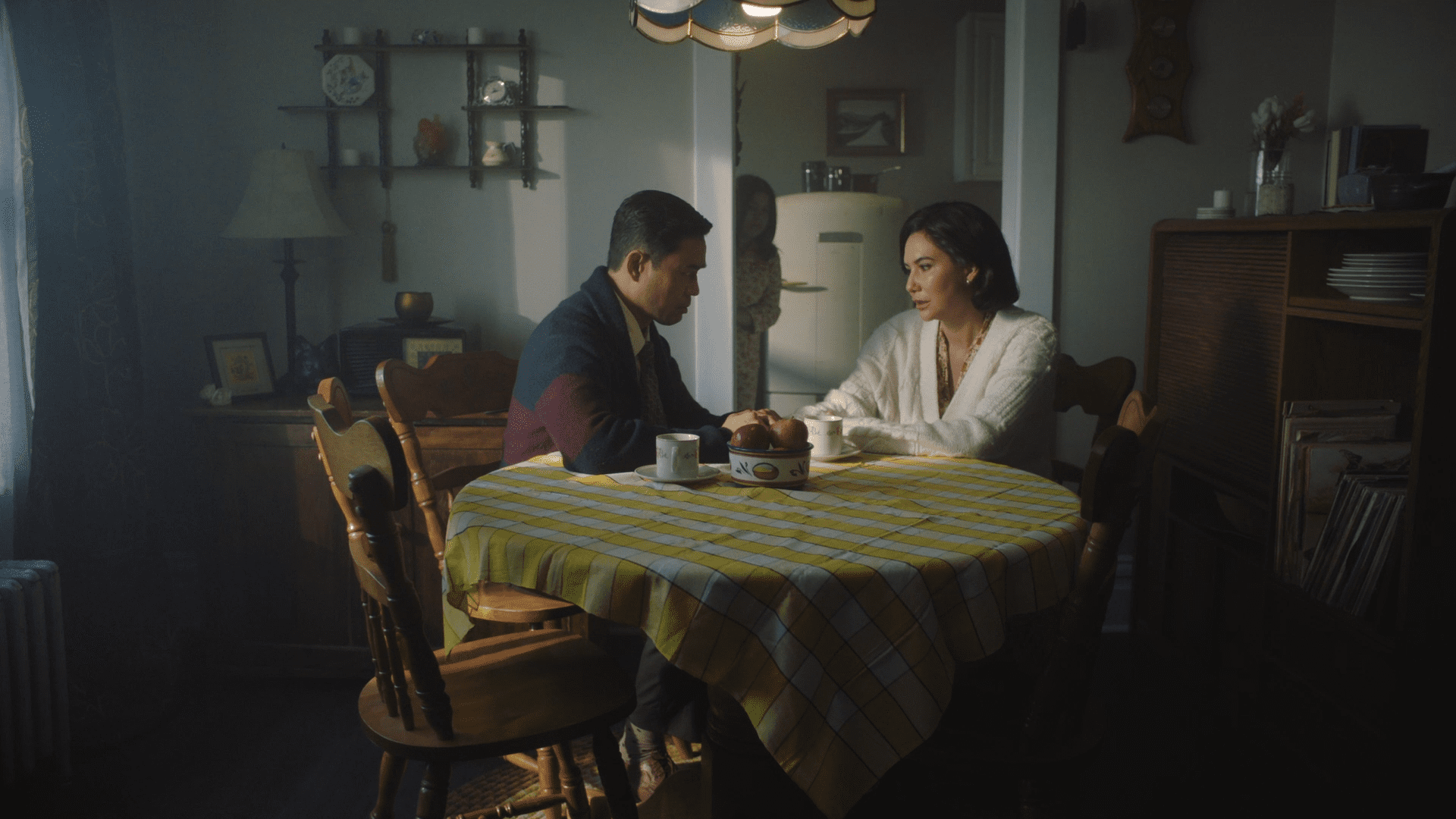

While all of this is taking place, there is also the world of the various Indian staff at the Viceroy?s House (the seat of the colonial government). We get into that ?downstairs? world through a love story involving Jeet Kumar (Manish Dayal), a new personal valet to Lord Mountbatten, and Aalia Noor (Huma Qureshi), the translator for Mountbatten?s daughter. Jeet and Aalia are from the same town, but because he is Hindu and she is Muslim, their romance has never been approved.

The interaction of these two perspectives to the historic events unfolding makes this a much more human story than a historical story. Although we see the disruptive and violent effect of Partition that displaced millions of people (and killed perhaps a million), we are emotionally drawn to the personal stories of Jeet and Aalia, and to a lesser extent of the Mountbatten family. It is the personal anguish that the decision to divide the nation?and in effect the lovers?that becomes the metaphor for the broader turmoil of Partition.

One of the interesting parts of this historical event is that for hundreds of years Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims all lived side by side?and were united in their opposition to the British Raj. But when independence became a possibility, the alliance seemed to break apart. (According to the film, this was secretly encouraged by the British government.) Neighbors whose families had coexisted for generations now had to choose their allegiance.

Although set in a history of seventy years ago, the film mirrors issues that continue to vex the world. We allow divisions between people to be the norm in many ways. We see it in the racial conflicts in the US, in the anti-immigrant movements here and in Europe, in the targeting of synagogues and mosques for vandalism and terrorism. In the film we hear Gandhi state, ?All religions are true. We are brothers of one soul.? Gandhi strongly opposed Partition. He believed that even though we have serious differences, we must learn to live together and to love one another. Yet in seventy years we do not seem to have learned how to overcome those divisions. Perhaps because we fail to see that we are indeed brothers and sisters of one soul.

Photos courtesy of IFC Films